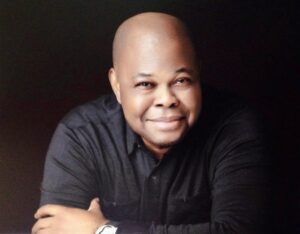

Special to USAfrica magazine (Houston) and USAfricaonline.com, first Africa-owned, US-based newspaper published on the Internet.

Dr. Okey Anueyiagu, public policy analyst and author of the book ‘Biafra, The Horrors of War, The Story of A Child Soldier’, is a contributor to USAfrica.

Many years ago I had gone to my village of Amudo – the land of peace, in my erstwhile beautiful town of Awka to visit with my father who was fast approaching his 100th year on earth. I always looked forward to visiting Awka, not because of the love one should have for ones home town, because this town, in the hands of our politicians, had decayed and deteriorated both in infrastructure, and in morals, but for the opportunity of spending time with my old man, and drawing from his deep well of history, knowledge, and wisdom. Upon driving into Awka, I was repulsed by the disorder and stench that had overtaken the town. Beyond the hustle and bustle that was the order of things, the town looked worse than it did right after the civil war when the Nigerian troops burnt down almost all the houses in the town, killed all the indigenes that

did not flee from the invasion. As we drove through the town, I held my fingers to my nostrils to ward off the acrid irritating stench from the overflowing piles of

refuse on the bumpy roads. Entering my father’s house was comforting and soothing. It was a far cry from the madness on the streets. I was reassured about being in the presence of my beginning. As usual, my father’s home was filled with visitors with each bearing their heavy burdens which they constantly, without

ceasing, offloaded on the old man. He never complained about this, as he would take his turn to listen and attend to each and everyone of these visitors. My

father always found a space in his heart and in his pockets to accommodate and carter to the needs of these villagers.

On this day, a particular woman caught my attention. She was an old aunty who was nearing 90 years and was a very distinguished retired teacher. She had lost

her brilliant son who attended the great Imperial College in London qualifying with a First Class degree in Petroleum Engineering. This cousin of mine had died

in an oilfield accident working with one of the large oil majors. His death was a great blow to our family, and a total devastation to his mother. As she began to

speak to me, her voice was strong and carried with it a feeling and sense of deep and penetrable anguish and torment; the types that can reap someone’s heart

straight through the chest. She came by her sorrowful but strong voice with absolute honesty and candor. She was telling me about her son and what his

absence has caused her. My aunty’s speech suddenly turned into a sermon that was dramatic as it wasprofound. She veered off from talking about the pains and agonies of loosing a loved one who was a provider and an only hope of sustainance, to telling me about hunger, misery and desolation in our village. I was drawn to tears as she

told me that many mothers, widows, and even the employed have forgotten how beef or even goat meat tastes. That their only source of protein, if one was

lucky, was through cheap tasteless frozen, and often spoiled fish. She began to talk about how many were dying in silence, and how pride which is an abiding

virtue of every Igbo, would not allow the poor and needy ones to beg for food and essential medicine. My aunty began to speak and advocate for the poor and

hungry in our village – whose conditions have been made worse and unbearable by the neglect of government to provide jobs and other social amenities to take

care of the old and needy.

This old lady’s sermon disturbed and agitated my mind, but it reinforced my long-held belief that we must all give to the poor and needy to uplift them from

such hopeless conditions as was being narrated by my aunty. I believe that we must give something, no matter how small, to the ones who have nothing and

need our assistance – for it is never too small in the eyes of those who truly do not have and are deserving of what we give. I learnt a long time ago, that

whatever we give is never too small in the eyes of God, and that when we give willingly, freely and silently, that this same God will give us abundantly in return.

The reflection from this visit to my father’s home, and my aunty’s tearful invocation of the hardship and misery of being poor in my village, became the

signpost that further strengthened my philanthropy that had long been in existence since I began to recognize the critical elements of the neglect our

society and its leaders have foisted on our people for decades. My rapid awareness of these maladies awakened in me, the spirit of giving and

my zeal of philanthropy. I believe that no form of human endeavour will thrive without a well-secured liberty and happiness that create value in people, and that the strength of any strong and progressive society must be attributed to the habit of the heart; the sum of moral disposition to public responsibility over selfish interest. This

implies that we must turn from our private interests and invest in the future, by implementing the ideas and realities about the need and our duties to

generously give to those in need.

My Okey Anueyiagu Foundation – www.okeyanueyiagufoundation.org, became my private intervention in many villages and towns in my bid to support the

upliftment of the quality of life and existence of many. We began to build portable health centers, schools and other infrastructural facilities. We began to

provide food items and other amenities to despondent and poor villagers. Our Foundation became an advocate for causes and matters that positively affect

the conditions of the poor and needy. By writing this short essay, I am hoping that I will inspire others to pursue, even in smaller ways, the passion of giving especially in this season of Christmas, as I believe that every one of us is gifted by God with talents to support one another, and that we can all perform small miracles in each other’s lives by giving to the poor and needy.